"ROCKETMAN" review

- Fergus Campbell, Staff Writer

- Jun 22, 2019

- 5 min read

One problem with liking film criticism is that you spend hours reading reviews instead of going outside, or making a decent lunch, or watching movies and judging them yourself. I may be the only person in America who has not yet seen Bohemian Rhapsody, simply because so many critics said that the film dulled, sanitized and straight-washed Freddie Mercury’s life, that it was merely a feat of damage control following a chaotic production. This negative critical reception (and my abstinence) apparently went unnoticed, because Bohemian Rhapsody plowed on and on and on, first to glorious opening weekend box office, then inexplicably high international grosses, a Golden Globe for Best Drama, and two Academy Awards, off five nominations.

I am torn about the success. On the one hand, the Globes win was a return to form for the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, traditionally a voting body that gushes over star power in spite of mediocrity, but which has recently been rewarding good filmmaking. (It’s fun, on some level, to believe in the invincible industry establishment.) It was also nice that Bohemian Rhapsody succeeded in the Rotten Tomatoes era, when consumers see low scores on rating sites—whose aggregation processes are arguably flawed—and skip movies they probably would have liked. On the other hand, I believe and respect the critics—many of whom avoid pretension or pickiness—telling me that Bohemian Rhapsody wasn’t any good, so the film’s commercial explosion in the face of their dissuasion is kind of sad. Disney has built its Marvel empire out of indie directors’ visions, who they wouldn’t have hired without critics’ opinions.

What’s the relevance of all this to Rocketman, the new Elton John biopic? Well, the film is doubtless a reaction to Bohemian Rhapsody’s commercial performance, and that of recent music-driven hits, like A Star Is Born and The Greatest Showman. (The film’s director is Dexter Fletcher, who handled Bohemian Rhapsody after the departure of Bryan Singer.) There now seem to be enough films of the sort to constitute a subgenre, and Rocketman’s construction might signal the trends and formulas to come. Call it the Music-Video-As-Movie, that cinematic delicacy which strings together half a story in service of long montages, which audiences would sooner watch on YouTube as individual clips. A Star Is Born almost differentiates itself from this setup, except that its legacy has been boiled down to “Shallow” (whether belted in a parking lot or on stage). And I’m not defining the subgenre out of dislike—it can prove as much of an enjoyment as the best studio rom-coms and no more of a diversion than most superhero pictures—but Rocketman inevitably adheres to it, even if in the process the film finds ways to wedge in moments of queerness and weird excess and bliss.

These moments come, without exception, when the best songs play. John’s belly-flop into a swimming pool, a scene that dominated the film’s trailers, leads to a glorious underwater interlude, where he swims toward his younger self, who sits at a miniature piano in astronaut garb, strings flourishing to accent the half-tempo first verse of the film’s title song. Rocketman uses set pieces like the pool repeatedly—as it covers John’s childhood through the first decade or so of his career—to aestheticize the artist’s inner monologue, from the neglect he feels growing up to the sense he gains as a teenager of his own potential, to his emotional waywardness and suffocation in the midst of peak popularity. Though the visuals deliver, they also possess an annoying sense of self-satisfaction. I felt I could see Fletcher and the film’s crew patting themselves on the back for the tracking shots and spiffy choreography at a suburban carnival, for the levitation of the crowd during John’s concert at the Troubador in Los Angeles. Yes, these scenes struck me as unconventional, but only in the context of narrow studio standards. It doesn’t help that during press tours, in an exhaustive effort to emphasize the film’s differences from other biopics, the film’s cast and crew talked about how they “didn’t deal with the songs in a chronological order,” and that there were “elements of fantasy.” Revolutionary? I think not. Compound this rather overhyped uniqueness with the fact that so many aspects of the film scream tradition—the endless static establishing shots, the bluntly telegraphed motivations—and one starts to wonder what would happen if people like Sam Levinson and his Euphoria team had handled the reality-distorting sequences, what that freshness of perspective might look like.

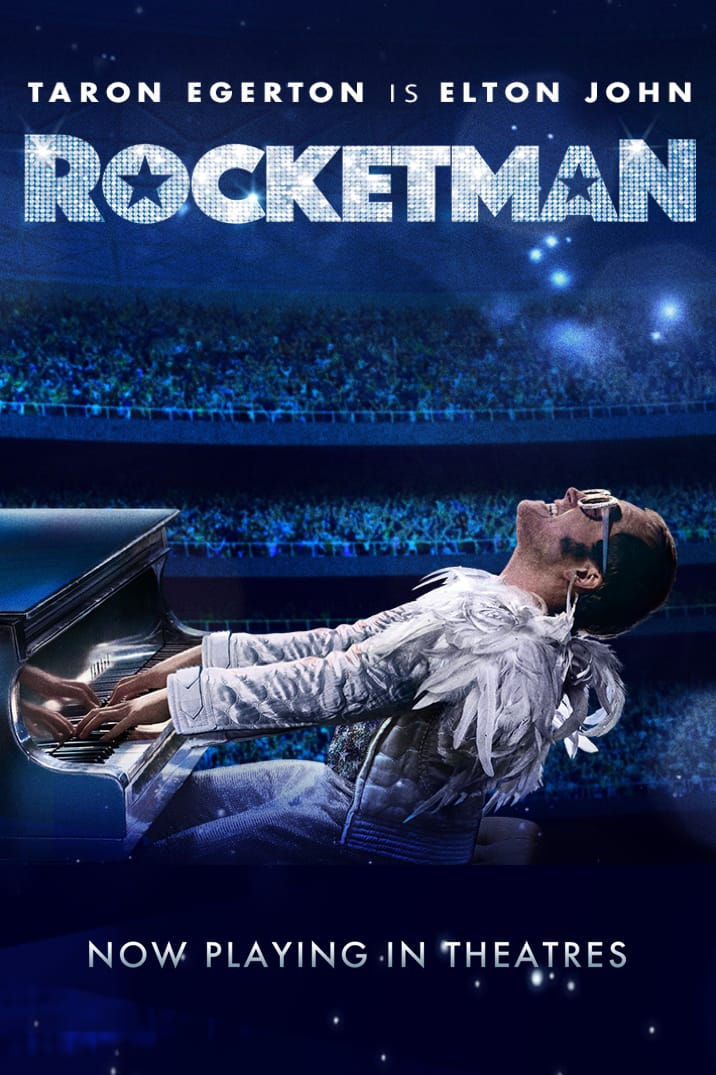

The songs in Rocketman are actually sung by Taron Egerton, who hopes to vault onto the A-list with a role that has been publicized as if he already occupied it. “Taron Egerton is Elton John,” read subway posters from New York to Paris, in glittering caps-lock. The guy from...Eddie the Eagle, right? Egerton might indeed deserve to be boldface famous—in his performance, he emotes intensely, and with every gesture, from the small smiles to shoulder shrugs. You get the sense that this Elton John feels a whole lot, even if he’s not very different from the persona John has been constructing for decades. Egerton’s authenticity is somewhat undermined by his physical attractiveness, because the film depicts him as a victim, of romantic partners’ betrayals and general loneliness, but with that jawline, that muscularity, this is hard to believe. It’s easy to forgive, though, especially when John Reid looks like Richard Madden, spray-tanned to the point of Mediterannean-ish ethnic ambiguity, in strange contradiction with the real Reid’s English pastiness.

I think the structure and effect of Rocketman indicate two directions for the future of similar films, and they’re not mutually exclusive. The first is the inspirational-sports-drama direction, or that of unsuccessful Oscar bait: pair a historical crash course with good actors and gloss to hide the ugly stuff (or most of it). Yes, we see John swallowing a handful of pills and winding up in the hospital. Yes, we see Reid seduce him after a party at a Hollywood estate that looks like it was invaded by Urban Outfitters. But addiction is not one overdose and gay sex is not two men making out for thirty seconds before the camera tilts away from them toward the ceiling. I can imagine the Rocketman crew telling me the film is about suggestion, but I don’t buy it. Multiple displays of graphic passion or substance abuse or androgyny are needed before a film can claim to meaningfully serve the LGBTQ community.

The second direction is concerning in a way that extends beyond cinematic integrity on its own terms. Rocketman, as with Bohemian Rhapsody, serves ultimately as an advertising vehicle for a big brand—a famous musician’s content library—and while Freddie Mercury was not alive to inform his on-screen portrayal (Queen’s remaining members handled that), Elton John, intimately involved with the film’s production (and really, he couldn’t not be), exerted control over the final projection of his personality. It doesn’t feel right that we should see a star exactly as he wants us to, because when is such a depiction ever accurate? But Rocketman’s success, though far inferior to Bohemian Rhapsody’s, will now signal to producers and studio executives that the rules for that music-video-movie subgenre are now established, and should be followed. At least we can dance to hit singles while that happens.

Fergus Campbell is a sophomore in Columbia College.

Comments